The story has become a familiar one in recent months.

The son of a south Wales coalminer is nurtured for super stardom by a dedicated schoolmaster.

The story of Richard Burton has been retold many times in a number of ways.

But recent celebrations to mark 100 years since the legendary actor’s birth reminded me of the discovery and development of another Welsh icon - Gareth Edwards.

The successful film “Mr Burton” tells the story of the young Richard Jenkins’ acting potential being spotted and honed by Port Talbot schoolteacher Philip Burton.

Such was Burton’s influence on the young actor, he became his legal guardian.

Richard even adopted Burton’s surname as it was more likely be accepted in theatrical circles rather than the more Welsh working class name of Jenkins.

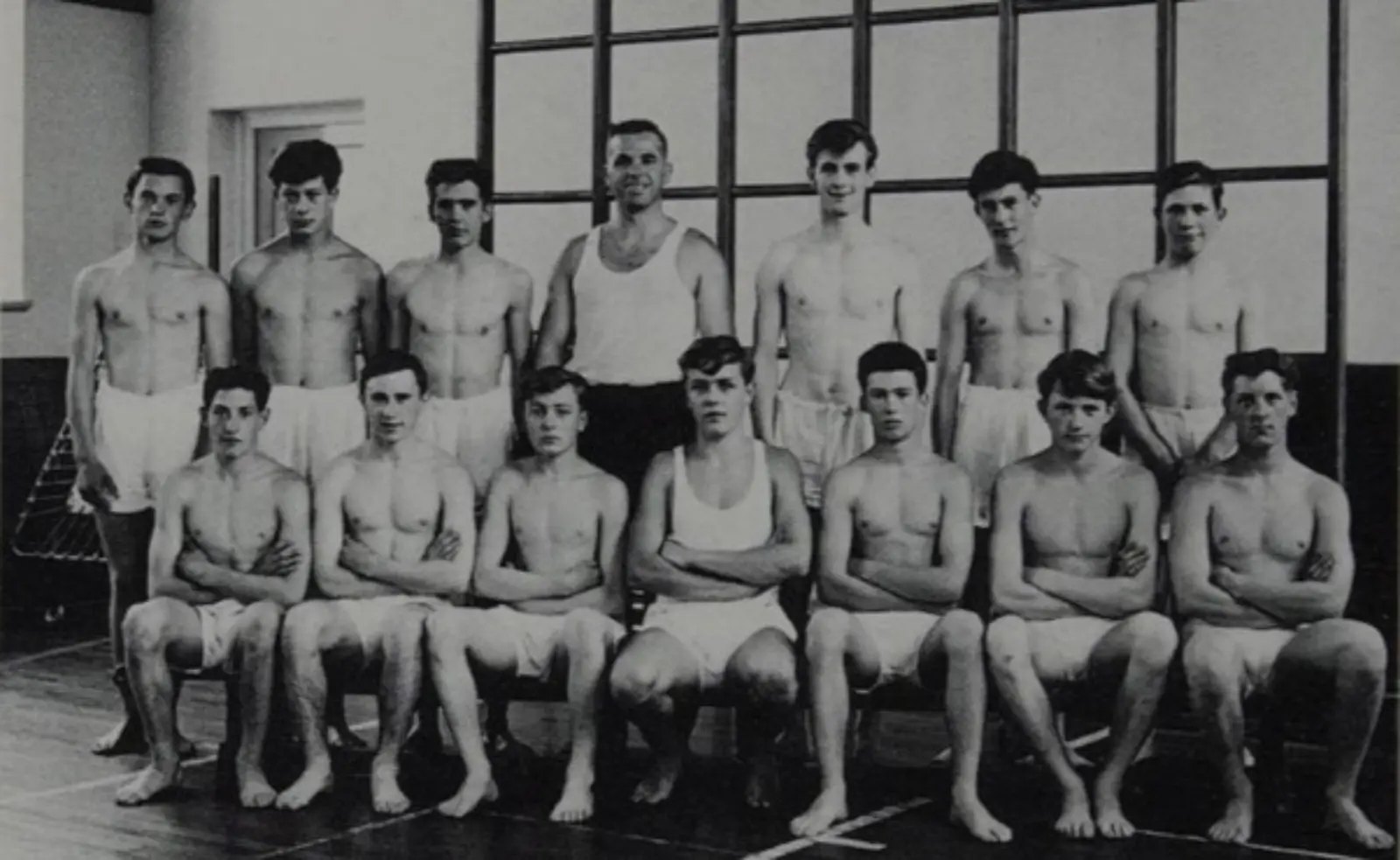

Ponty Tech gym team with Bill Samuel in the back rown and Gareth Edwards far left in the front row.

The rest, as they say, is history. Richard Burton went on to become a global star of stage and screen.

Similarly, a young Gareth Edwards’ previously unrecognised rugby talents were identified and finessed by Bill Samuel, a teacher at the grandly titled but modestly sized Boys’ Secondary Technical School and College of Further Education in Pontardawe.

It was more popularly known as Ponty Tech.

Edwards’ development is journaled in Samuel’s book Rugby: Body and Soul, described as a brilliant characterisation of Welsh Valleys life when it was originally published in 1986.

Fate brought Samuel and Edwards together in 1961 on the 13-year-old’s arrival at Ponty Tech, having earlier failed his 11-plus exams.

When the sports-mad Edwards put himself forward for a Swansea Valley District Rugby Union Under-15 trial match as a centre, there was little evidence he would become one of the world’s all-time great players.

Weighing in at eight-stone five pounds and measuring five foot three inches in his stockinged feet, Edwards was described as “Lilliputian” in comparison to his midfield rivals during the trial.

Such was the disparity in size, the youngster, whose playing hero was Wales and British Lions centre Bleddyn Williams, was withdrawn from the field for his own safety.

"It's like a Pembrokeshire corgi wanting to be a sheepdog," Samuel told his diminutive but hugely enthusiastic and energetic pupil.

"It cannot be done."

However, the former St Luke’s College, Cardiff and Llanelli wing-cum-full back, who had an uncanny eye for matching novice players to their optimal rugby positions, had spotted something in the teen and suggested he become a scrum half.

“I’ve never played in that position before, sir,” replied Edwards, who was from the nearby mining village of Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen in the neighbouring Amman Valley.

To which Samuel countered: “Well, you are never too old to learn, are you?

"We can start from scratch. I’ll make you into one.

"We have produced many a Swansea Valley scrum-half in our school, you know.

“We’ll start this afternoon in the games lesson, and stay behind for an hour after school. Mark my words, you’ll be playing for the district within a month.”

And so began Edwards’ transformation from undersized centre to one of the true giants of the world game under the tuition of the man known locally as Bill Sam.

Master and apprentice became an almost inseparable sporting partnership over the next few years.

With Samuel living in the neighbouring village of Cwmgors, Edwards would cross his path on an almost daily basis, inside and outside the school gates.

In Rugby: Body and Soul, hailed as one of the best rugby books of all-time by the likes of renowned rugby journalist Stephen Jones, Samuel recalls: “I taught him maths, English, scripture and PE, nearly half his weekly timetable.

“In addition, he was a member of my Urdd gymnastics club and also attended the Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen youth club twice a week where I was warden. He also followed my schedules during school holidays and weekends.”

Not only did the teenager develop as a rugby player with Samuel’s supervision, he displayed prowess as a gymnast, became a champion hurdler and attracted interest from Swansea Town and other football clubs.

While there was no need for guardianship or name changes for this son of a coalminer, Samuel did help his protégé off the pitch as well as on it.

Just as Philip Burton did everything in his power to get the young Richard into Oxford University, Samuel moved Heaven and Earth to get Edwards into Millfield School.

At the time, Millfield was the most expensive fee-paying school in the UK and renowned for developing prodigious sporting talent.

As Edwards’ time at Ponty Tech was about to come to an end with the sitting of his O levels, Samuel was concerned about his future education and sporting development.

As a result, he wrote a speculative letter to Millfield’s headmaster RJO Meyer, the former Somerset County Cricket Club captain, enquiring about the possibility of a sporting scholarship at the school.

Meyer initially informed Samuel that his school did not provide sporting scholarships, but a flurry of correspondence ensued.

Such was the regularity of their missives, originally formal in their nature, the two men came to address each other as ‘Dear Bill’ and ‘Dear Jack’.

An agreement was eventually arrived at. The school covered part of the fees, a mystery benefactor sourced by Meyer added a contribution, and Edwards’ parents met the remainder.

It meant the Edwardses worked extra hours and additional jobs. The family caravan in Porthcawl also had to be sacrificed, but their son was on his way to Millfield.

And so it was that the coalminer’s son from a modest council house in Colbren Square, Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen, found himself at the famous Somerset school alongside the sons and daughters of royalty, aristocracy, and film stars.

Edwards thrived. The school’s reputation and enviable facilities helped him fulfil the potential he had shown at Ponty Tech, where only one hurdle was available for the budding athlete to practice with.

Lessons from the life of Bill Samuel

The ultimate sporting all-rounder became English schools hurdles champion, breaking the British record on the way.

He also enjoyed the distinction of beating Alan Pascoe, who would go on to compete at the Olympics three times for Great Britain.

When his star student left Millfield, Meyer wrote to Samuel saying: “Gareth, alas, has moved on, the better I hope for his days at Millfield.

"I doubt if I shall see his like again, for all the top class performers in various fields of school activity, he was on his own.”

Edwards, of course, went of to become one of the finest players ever to pick up a rugby ball.

Capped in 53 consecutive Tests for Wales – a feat he attributed to the physical conditioning he underwent under Samuel’s tutelage – Edwards captained his country 13 times and scored 20 tries – a record at the time.

He also won seven Five Nations titles with Wales and three Grand Slams.

His international career, between 1967 to 1978, included starring roles in the victorious British and Irish Lions series in 1971 and 1974, having first toured in 1968.

In total, he played in 39 Lions matches, 10 of which were Tests.

The boy from Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen who found fame on the global stage has never forgotten the man who helped him achieve his dreams.

Edwards once said of Bill Sam: “I often wonder what would have happened to me if good fortune had not blessed me with his presence.”

Three days before Samuel died in November of 2002, Edwards was voted the greatest ever Welsh rugby player by Western Mail readers.

The following year, the scrum-half was voted the greatest player of all-time in a poll of international players conducted by Rugby World magazine.

Not bad for a failed centre three-quarter who was taken under the wing of a sports master at a small technical college in the Swansea Valley.

Perhaps someone will make a film about it one day.